Every year, thousands of people in the U.S. and UK end up in the hospital not because of a virus or bad diet, but because of a medicine they were told was safe. This is drug-induced liver injury - or DILI - and it’s one of the most dangerous, yet overlooked, side effects of common drugs. It doesn’t always show up right away. Sometimes it takes weeks. Other times, it sneaks in quietly, with no symptoms until your liver is already badly damaged.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Liver Injury?

DILI happens when a medication, herbal supplement, or even a vitamin harms your liver. It’s not the same as alcohol damage or fatty liver disease. This is liver injury caused by something you took on purpose - often because your doctor prescribed it. The liver is your body’s main detox center. It breaks down drugs, but sometimes, the breakdown process creates toxic byproducts that attack liver cells instead of clearing them safely.

There are two main types. The first is intrinsic - predictable and tied to dose. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the classic example. Take too much, and your liver gets hit hard. The second is idiosyncratic - unpredictable. It can happen to one person but not another, even if they take the same dose. This type makes up about 75% of all DILI cases and is much harder to spot before damage is done.

Which Medications Are the Biggest Risks?

Not all drugs are equal when it comes to liver risk. Some are common, safe for most - but deadly for a small number. Here are the top offenders:

- Acetaminophen - The #1 cause of acute liver failure in the U.S. A single dose over 7-10 grams can be toxic. Even regular doses, especially in older adults or people with existing liver issues, can build up to dangerous levels. The recommended max is 3 grams per day for high-risk groups.

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin) - This common antibiotic causes more idiosyncratic DILI than any other drug. About 1 in every 2,000 to 10,000 people who take it develop liver injury. Symptoms like yellow skin, dark urine, and intense itching can show up weeks after finishing the course.

- Valproic acid - Used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, it can cause severe liver damage, especially in children under 2 or those on multiple seizure meds. Fatality rates in severe cases hit 10-20%.

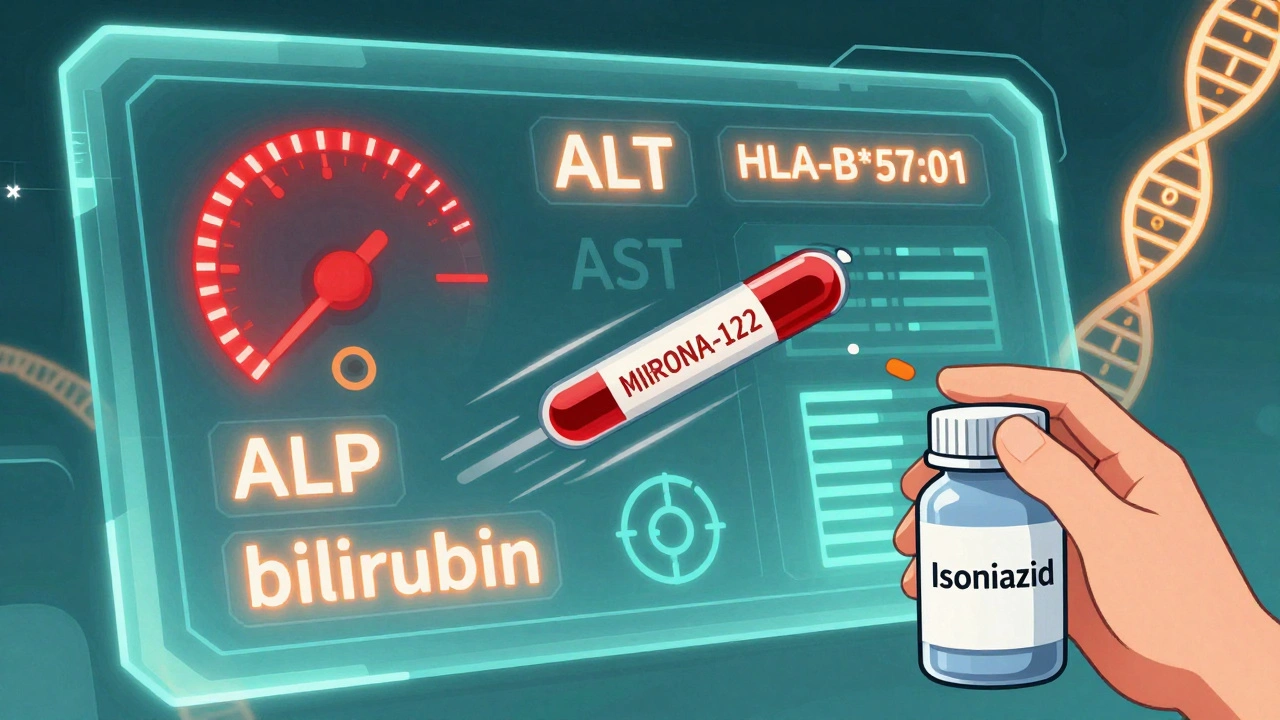

- Isoniazid - A tuberculosis drug that’s been around for decades. About 1% of users get liver injury. Risk jumps to 2-3% if you’re over 35. Many don’t realize the danger until their ALT levels spike above 1,000.

- Herbal and dietary supplements - These aren’t just harmless teas or pills. Green tea extract, kava, anabolic steroids, and weight-loss products are now responsible for 20% of DILI cases in the U.S. - up from just 7% in the early 2000s. Many people think “natural” means safe. It doesn’t.

Statins, often blamed for liver damage, rarely cause serious injury. Less than 1 in 50,000 users develop severe hepatotoxicity. Mild ALT elevations are common, but they’re usually harmless and don’t need stopping.

How Do You Know If It’s DILI?

There’s no single test. DILI is a diagnosis of exclusion - meaning doctors have to rule out everything else first: hepatitis A, B, C; autoimmune disease; alcohol use; gallstones. The key clues come from blood tests and timing.

Doctors look at two main liver enzymes:

- ALT (alanine aminotransferase) - If this is more than 3 times the normal upper limit, it usually means liver cells are being destroyed.

- ALP (alkaline phosphatase) - If this is more than 2 times normal, it suggests bile flow is blocked - often from drugs like amoxicillin-clavulanate.

The pattern tells the story:

- Hepatocellular - High ALT, normal or slightly high ALP. Think acetaminophen overdose.

- Cholestatic - High ALP, normal or only slightly high ALT. Think antibiotics or birth control pills.

- Mixed - Both are elevated. Common with many herbal supplements.

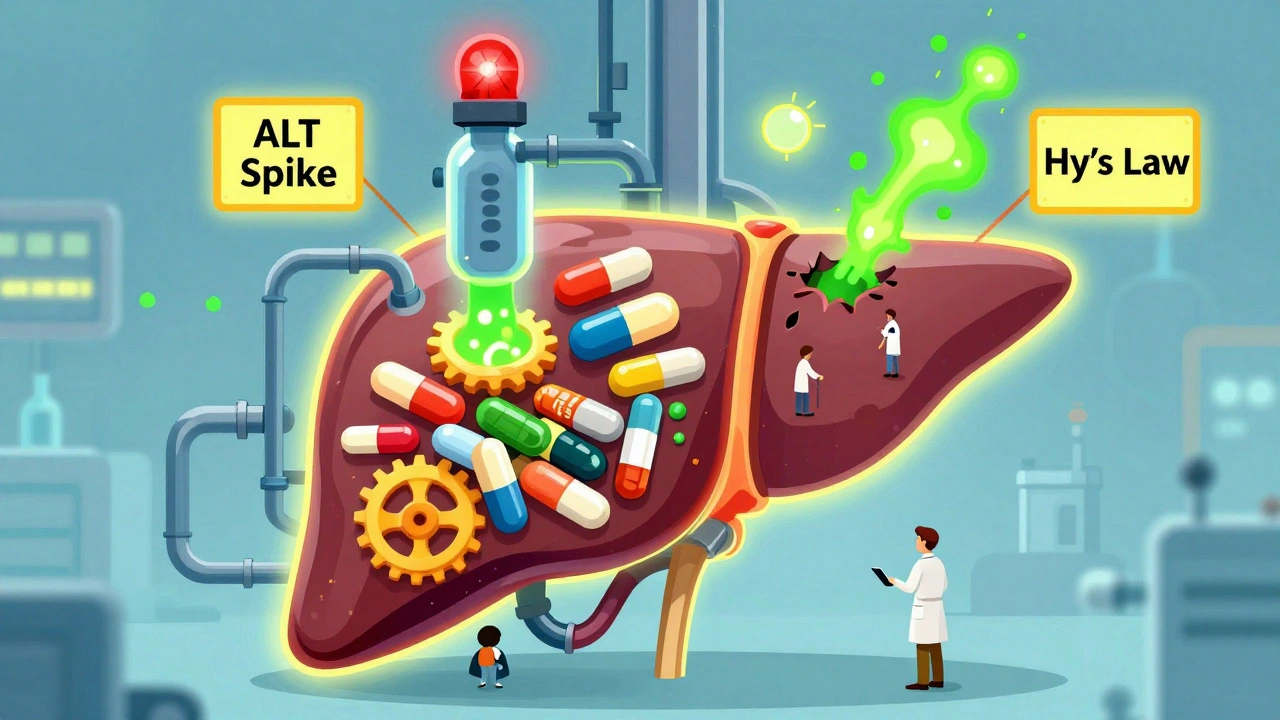

There’s also Hy’s Law - a red flag that’s hard to ignore. If your ALT or AST is over 3x the upper limit AND your bilirubin is over 2x normal, you have a 10-50% chance of developing acute liver failure. This isn’t a minor lab result. It’s an emergency.

Who Gets It - And Why?

DILI doesn’t pick favorites, but some groups are more vulnerable:

- Women - Make up about 63% of cases. Why? Hormones, metabolism differences, and possibly immune response.

- People over 55 - Liver function slows with age. Detox pathways aren’t as efficient.

- Those on multiple medications - Polypharmacy increases interaction risk. A cholesterol drug + an antibiotic + a supplement? That’s a recipe for trouble.

- People with pre-existing liver disease - Even a small dose of acetaminophen can tip them into failure.

Genetics play a role too. Scientists have found specific gene variants that make certain people far more likely to react badly. For example, carrying the HLA-B*57:01 gene increases your risk of liver injury from flucloxacillin by over 80 times. HLA-DRB1*15:01 raises your risk for amoxicillin-clavulanate injury by 5.6 times. Genetic testing isn’t routine yet - but it’s coming.

How to Monitor for DILI - Step by Step

Prevention beats treatment. Here’s how to stay safe:

- Get a baseline liver test - Before starting any high-risk drug (isoniazid, valproic acid, certain antibiotics), ask for ALT, AST, ALP, and bilirubin. Keep a copy.

- Follow the schedule - For isoniazid, the CDC recommends monthly liver tests for the first 3 months, then every 3 months. For other high-risk drugs, weekly for the first month, then every 2 weeks for months 2-3, then monthly.

- Know the warning signs - Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, dark urine, yellow eyes or skin, itching, right-sided abdominal pain. Don’t wait for blood tests to catch these. If you feel off, get checked.

- Stop the drug immediately if signs appear - In 90% of cases, liver enzymes start improving within 1-2 weeks after stopping the culprit drug.

- Talk to your pharmacist - They’re trained to spot dangerous drug combinations. One patient’s pharmacist caught a deadly interaction between an antibiotic and seizure meds before the first pill was taken.

For statins, routine monitoring isn’t recommended - the risk is too low. But if you’re over 60, have diabetes, or drink alcohol regularly, ask your doctor if a baseline test is wise.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

If DILI is confirmed, the first step is always stopping the drug. That’s it. No miracle cure. No special pill. Just removal of the toxin.

For acetaminophen overdose, there’s one exception: N-acetylcysteine (NAC). If given within 8 hours of overdose, it’s nearly 100% effective at preventing liver failure. After 16 hours, it drops to 40% effective. Time matters.

Most people recover fully in 3-6 months. But 12% develop permanent damage. A small number - about 13% of all acute liver failures - end up needing a transplant. That’s why early detection is everything.

What’s Changing in DILI Detection?

Science is catching up. New tools are emerging:

- MicroRNA-122 - A blood biomarker that rises 12-24 hours before ALT. Could allow earlier detection.

- Keratin-18 - Measures liver cell death. Helps distinguish between mild and severe injury.

- DILI-similarity score - A computer model that predicts liver risk based on a drug’s chemical structure. It’s 82% accurate.

- EHR alerts - Hospitals are starting to build automated warnings into electronic records. If you’re prescribed isoniazid and you’re over 40, the system flags your chart. Early data shows this could prevent 15-20% of severe cases.

The FDA now requires drugmakers to test for mitochondrial toxicity during development - something that caused the failure of drugs like troglitazone in the past. Regulations are tightening, but patients still need to be their own advocates.

Real Stories, Real Risks

A 45-year-old woman in the UK took Augmentin for a sinus infection. Three weeks later, her eyes turned yellow. She was told it was “just a virus.” It took three doctors and three months to connect it to the antibiotic. Her liver took six months to recover.

A man in his 60s took isoniazid for TB. His ALT jumped to 1,200 (normal is under 40). He didn’t have symptoms. His doctor didn’t check his liver. By the time they did, he was days from liver failure.

On Reddit, someone wrote: “It took four doctors and three months to realize my cholesterol pill was killing my liver.”

These aren’t rare. They’re common - and preventable.

Bottom Line: You Can Protect Yourself

Drugs save lives. But they can also break your liver - quietly, without warning. The key isn’t avoiding medicine. It’s being smart about it.

- Ask: “Is this drug linked to liver injury?”

- Get a baseline blood test before starting high-risk meds.

- Know your symptoms - don’t wait for a lab report.

- Don’t assume herbal supplements are safe.

- Use a pharmacist as a second pair of eyes for drug interactions.

If you’re on long-term medication - especially for epilepsy, TB, or high cholesterol - talk to your doctor about liver monitoring. It’s not paranoia. It’s prevention. And it could save your life.

Can over-the-counter painkillers cause liver damage?

Yes. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is the leading cause of acute liver failure in the U.S. Taking more than 3 grams per day - especially if you drink alcohol, are over 65, or have liver disease - can be dangerous. Even normal doses can build up over time. Always check labels on cold and flu meds - many contain acetaminophen too.

Are herbal supplements safer than prescription drugs for the liver?

No. Herbal and dietary supplements now cause about 20% of all drug-induced liver injury cases in the U.S. - more than antidepressants or NSAIDs. Products like green tea extract, kava, and weight-loss pills can be just as toxic as prescription drugs. They’re not regulated like medications, so their safety isn’t proven. “Natural” doesn’t mean safe.

How long does it take for the liver to recover from drug damage?

Most people see improvement in liver enzymes within 1-2 weeks after stopping the drug. Full recovery usually takes 3-6 months. But about 12% of cases result in permanent liver damage. In rare cases, it leads to liver failure requiring a transplant. Early detection is the biggest factor in recovery.

Should I get my liver checked before taking antibiotics?

Routine testing isn’t needed for most antibiotics. But if you’re taking amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin), are over 55, have a history of liver disease, or are on other medications, ask your doctor for a baseline liver test. The risk is low, but the consequences can be severe. Symptoms like itching, dark urine, or yellowing skin should be checked immediately - even if you’ve finished the course.

Can genetic testing predict if I’ll get drug-induced liver injury?

For a few specific drugs, yes. Genetic testing for HLA-B*57:01 is recommended before prescribing flucloxacillin in some countries. For amoxicillin-clavulanate, HLA-DRB1*15:01 testing is being studied. But these tests aren’t widely available yet. Most DILI is still unpredictable. That’s why monitoring and symptom awareness remain the best tools.

What should I do if I think a medication is hurting my liver?

Stop taking the drug immediately and contact your doctor. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. Get blood tests for ALT, AST, ALP, and bilirubin. Bring a list of all medications and supplements you’re taking - including herbs and vitamins. If you have jaundice, confusion, or severe fatigue, go to urgent care or the ER. Early action saves lives.

9 Comments

Carolyn Ford

December 4 2025

I’ve seen this before-another ‘medical authority’ scaring people into thinking their meds are poison. And yet, you conveniently omit the fact that 99.9% of people who take amoxicillin-clavulanate don’t get liver damage. Meanwhile, your article ignores the fact that *alcohol* kills more livers than every prescription drug combined. You’re not educating-you’re weaponizing uncertainty. And for what? To make people skip their antibiotics? That’s not prevention. That’s negligence dressed up as wisdom.

Pavan Kankala

December 5 2025

You think this is about liver damage? Nah. This is about control. The FDA, the AMA, the pharmaceutical giants-they want you to believe you’re too stupid to know what’s safe. That’s why they make you get blood tests before every antibiotic. Why? Because they don’t want you to self-diagnose. They want you dependent. And don’t even get me started on ‘natural supplements’ being blamed. Who do you think owns the patents on all those ‘dangerous’ herbs? Big Pharma. They buy the farms, then label them ‘toxic’ so you buy their synthetic pills instead.

Yasmine Hajar

December 5 2025

I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen people ignore the signs until they’re in the ER with jaundice and confused as hell. I’ve held the hands of people who thought ‘natural’ meant ‘no consequences.’ I’ve seen 70-year-olds on 12 meds who didn’t know their Tylenol was in their cold medicine too. This isn’t fear-it’s love. It’s saying: ‘I care enough to tell you the truth, even if it’s uncomfortable.’ If one person reads this and asks their doctor for a blood test before starting isoniazid? That’s a life saved.

Karl Barrett

December 7 2025

The pathophysiology of idiosyncratic DILI remains profoundly heterogenous, with mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and immune-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis as the primary mechanistic axes. The HLA associations-particularly HLA-B*57:01 and HLA-DRB1*15:01-demonstrate a compelling gene-environment interaction, yet current clinical practice remains woefully reactive rather than preemptive. The emerging biomarkers-miR-122, K18, and metabolomic profiling-represent a paradigm shift toward predictive hepatotoxicity assessment, but their integration into EHRs remains fragmented due to reimbursement inertia and lack of standardized protocols. We are on the cusp of precision hepatology-but only if we stop treating DILI as an outlier and start treating it as a systems failure.

Jake Deeds

December 9 2025

I mean, honestly, if you’re taking herbal supplements, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with your organs. And yet, people post on Instagram about their ‘cleanses’ like it’s a lifestyle brand. I had a cousin who took ‘detox tea’ for three months and ended up in the hospital. Her doctor said, ‘I’ve never seen a liver look like that from anything except alcohol or acetaminophen.’ She didn’t even drink. She just believed in magic powders. This isn’t medicine-it’s cult mentality with a side of chia seeds.

George Graham

December 10 2025

I just want to say thank you for writing this. My mom was on valproic acid for years and never had a single test. She got sick one day, and by the time they figured it out, her liver was already failing. She’s okay now-thanks to a transplant-but we lost a year of her life to ignorance. If this post saves even one person from going through that, it’s worth every word. Please keep speaking up. We need more voices like yours.

Augusta Barlow

December 12 2025

You know what’s really scary? That the FDA doesn’t require mandatory liver monitoring for *any* drug unless it’s already caused a dozen deaths. And the drug companies? They bury the data. I’ve got friends who worked at Pfizer who told me about the internal memos on isoniazid-how they knew the risk was higher in older adults but didn’t change the label because ‘it would hurt sales.’ And now they’re pushing ‘new and improved’ versions with the same toxic backbone. They don’t care about your liver. They care about your quarterly earnings. And they’ll keep selling until the next big scandal hits the news-and then they’ll just rebrand it as ‘safer.’

Jenny Rogers

December 13 2025

This is a textbook example of irresponsible medical journalism: conflating rare, idiosyncratic adverse events with systemic risk, while ignoring the overwhelming benefit-risk ratio of the medications in question. To suggest that baseline liver testing is universally warranted for antibiotics is not only unsupported by evidence, but actively harmful-it promotes unnecessary anxiety, increases healthcare costs, and diverts resources from proven public health interventions. The data are clear: DILI is exceedingly rare, and most cases resolve spontaneously upon discontinuation. To frame this as an epidemic is not only inaccurate-it is unethical.

Benjamin Sedler

December 4 2025

Look, I get it-acetaminophen is the villain of the week. But let’s be real: if your liver can’t handle a Tylenol after a long night, maybe your liver was already on vacation. I’ve been taking 4g/day for years, coffee with my morning pill, and I’ve got the liver of a 22-year-old rower. Your fear-mongering is just Big Pharma’s way of selling you ‘liver support’ gummies that cost $40 a bottle.