Acute interstitial nephritis isn’t something most people hear about until it hits them-or someone they know. It’s not a flashy disease, no dramatic symptoms like chest pain or sudden paralysis. But it’s quiet, sneaky, and increasingly common. And it’s mostly caused by medicines you probably take every day.

Imagine your kidneys as filters. Tiny tubes and spaces between them-the interstitium-get inflamed. That’s AIN. It doesn’t always show up on routine blood tests. It doesn’t always cause swelling or foamy urine. But it can knock your kidney function down fast. And if you don’t catch it early, the damage might stick around forever.

What Drugs Are Really Behind AIN?

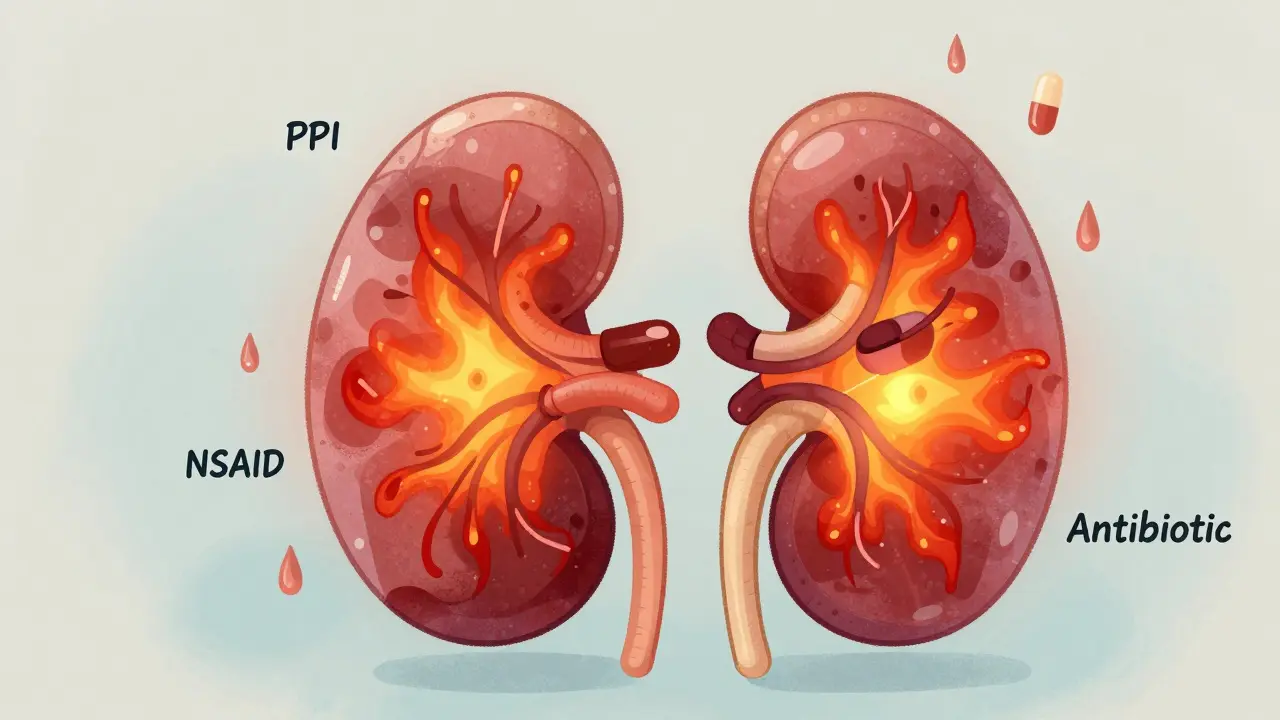

More than 250 medications have been linked to acute interstitial nephritis. But three classes stand out: antibiotics, NSAIDs, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). And the landscape has shifted.

Twenty years ago, penicillin and sulfa drugs were the usual suspects. Today, it’s PPIs-like omeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole-that are second only to antibiotics as triggers. In fact, about 12 out of every 100,000 people on PPIs develop AIN each year. That’s not rare. That’s a public health signal.

NSAIDs-ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac-are responsible for nearly half of all drug-induced AIN cases. But here’s the twist: they don’t always cause the classic signs like rash or fever. Instead, they sneak in over months. Someone takes ibuprofen daily for arthritis. After a year, their creatinine creeps up. They’re told it’s just aging. But it’s AIN.

Antibiotics still cause about a third of cases. Ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, cephalosporins-they trigger faster. Symptoms often show up within 10 days. And yes, some people get the full triad: fever, rash, eosinophilia. But that’s rare. Less than 10% of cases show all three. Most just feel tired, lose their appetite, or notice their urine has changed.

Why Is Diagnosis So Hard?

AIN doesn’t scream for attention. It whispers. Patients often go to their doctor with vague symptoms: nausea, low-grade fever, maybe a little joint pain. They’re told it’s a virus. Or a UTI. Or stress.

One patient on a kidney forum described going to the ER three times over three weeks. Each time, they were given antibiotics for a suspected UTI. Only after their creatinine hit 3.8-and they started needing dialysis-did someone think to ask: What meds are you taking?

That’s the problem. There’s no single blood test for AIN. Urine tests might show eosinophils, but that’s not reliable. A gallium scan? Too outdated. The only way to be sure is a kidney biopsy.

And that’s a hurdle. Many doctors hesitate. They think, Maybe it’ll get better on its own. But waiting costs time-and kidney function.

Experts agree: if you suspect AIN, don’t wait. If someone’s kidney function is dropping and they’re on a PPI, NSAID, or antibiotic, stop the drug immediately. Don’t wait for biopsy results. Delaying by more than two weeks cuts your chances of full recovery by almost half.

Recovery Isn’t Guaranteed-Even After Stopping the Drug

Stopping the medicine is step one. And it works. Most people start feeling better within 72 hours. Some see their creatinine drop in days.

But recovery isn’t the same for everyone.

With antibiotics, 70-80% of patients regain near-normal kidney function. That’s good news. But with PPIs? Only 50-60% recover fully. Even after stopping the drug, their kidneys never bounce back to where they were.

NSAIDs are the worst. Nearly 42% of patients end up with chronic kidney disease (stage 3 or worse) within a year. Why? Because NSAID-induced AIN often hides for months. By the time it’s caught, the inflammation has already started scarring the kidney tissue. And scars don’t heal.

One case from the American Kidney Fund tells the story: a 63-year-old woman took omeprazole for 18 months. When she was diagnosed, her eGFR was 18. She needed dialysis for three weeks. A year later, her eGFR was 45-still below normal. She’s not alone.

Even if you don’t need dialysis, you might be left with permanent damage. About 42% of patients in one survey had an eGFR under 60 six months after diagnosis. That’s not just a lab number. That’s a lifetime of higher risk for heart disease, hospitalizations, and faster decline.

Do Steroids Help?

This is where things get messy.

No large randomized trial has proven steroids work for AIN. But in practice, doctors use them anyway. Why? Because the stakes are too high.

If your eGFR is below 30, or your kidney function keeps dropping after three days off the drug, most nephrologists will start steroids. Typically, methylprednisolone at 0.5 to 1 mg per kg per day for two to four weeks, then slowly taper off over two months.

Dr. Ronald Falk, a leading kidney specialist, says it plainly: “We don’t have proof, but we’ve seen enough patients improve with early steroids to justify using them in severe cases.”

There’s no magic formula. Some patients get better without steroids. Some still decline despite them. But if you’re young, otherwise healthy, and caught early-steroids might be the difference between full recovery and lifelong kidney trouble.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

You’re not equally at risk for AIN. Age matters. So does how many pills you take.

People over 65 are nearly five times more likely to develop AIN than those under 45. Why? Kidneys naturally decline with age. And older adults are more likely to be on multiple medications-PPIs for acid reflux, NSAIDs for arthritis, antibiotics for infections.

Polypharmacy is the silent amplifier. Taking five or more drugs increases your risk of AIN by over three times. That’s not coincidence. It’s cumulative stress on the kidneys.

And here’s the kicker: many of these drugs are taken long-term without review. Someone gets prescribed omeprazole for heartburn after a hospital stay. They never go back to see if they still need it. Five years later, they’re on it daily. And their kidneys are quietly paying the price.

What Can You Do?

If you’re on a PPI, NSAID, or antibiotic and you’re feeling off-fatigued, nauseous, your urine looks different-don’t ignore it. Talk to your doctor. Ask: Could this be kidney-related?

Don’t assume it’s just aging. Don’t assume your doctor already checked.

Ask for a basic kidney panel: creatinine, eGFR, and urine dipstick. If your eGFR has dropped by more than 25% from your last test, that’s a red flag. Push for more.

If you’re on PPIs long-term, ask if you still need them. Many people take them for years when they only needed them for a few weeks. The same goes for NSAIDs. Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible.

And if you’ve been diagnosed with AIN? Stop the drug. Immediately. Don’t wait. Then follow up with your nephrologist. Track your eGFR every three months for at least a year. Recovery isn’t always linear. Some people plateau. Others decline slowly. You need to know where you stand.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. Scientists are testing new urine biomarkers-like CD163-that could replace biopsies. One study showed 89% accuracy in detecting AIN without a needle. That’s huge. If it works in wider populations, we could diagnose AIN in minutes, not weeks.

Meanwhile, drug regulators are paying attention. The FDA issued a safety alert on PPIs in 2021. The European Renal Association updated guidelines in 2023. But awareness among primary care doctors? Still lagging.

AIN is not rare. It’s not exotic. It’s a side effect of modern medicine. And it’s preventable-if we look.

9 Comments

TiM Vince

January 11 2026

I’m from a country where NSAIDs are sold like candy. No prescription. No warning. People pop them for headaches, back pain, menstrual cramps - daily. No one connects it to kidney health. This post should be translated and shared everywhere.

gary ysturiz

January 12 2026

Hey everyone, I just want to say this is so important. So many of us are on these meds without even knowing the risks. I used to take ibuprofen every day for my knee pain. Then I got tired all the time and my urine looked funny. I thought I was just getting old. Turns out my kidneys were screaming. Stopped the pills, got tested, and now I’m on a path to recovery. You’re not alone. And it’s never too late to turn things around. Small changes save lives.

Jessica Bnouzalim

January 13 2026

Okay, so I just found out my mom’s been on omeprazole for TEN YEARS because her doctor said "it’s fine" - and now her eGFR is 48?!?!? I’m literally shaking. We’re going to her doctor tomorrow. No more "just aging" excuses. This is NOT normal. Someone needs to scream this from the rooftops!

laura manning

January 15 2026

While anecdotal evidence may suggest a correlation between proton pump inhibitor use and acute interstitial nephritis, the absence of large-scale, randomized, controlled trials precludes definitive causal attribution. Furthermore, confounding variables - including age, polypharmacy, and preexisting renal insufficiency - must be rigorously controlled in any epidemiological analysis. To imply that PPIs are a primary driver of AIN without such evidence constitutes premature clinical generalization.

Bryan Wolfe

January 16 2026

Thank you for sharing this. Seriously. I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen too many patients told "it’s just your age" when their kidneys were failing. I had a patient last year - 72, on 7 meds, including PPI and naproxen - she thought she was just "feeling off." We stopped the drugs, started steroids, and she’s back to gardening. Don’t wait. Ask. Push. Advocate. Your kidneys are working for you - don’t let them down.

Sumit Sharma

January 16 2026

These statistics are not surprising. Western medicine overprescribes. PPIs are prescribed like vitamins. NSAIDs are treated as aspirin. No one teaches medical students about drug-induced nephrotoxicity in primary care. The system is broken. Patients are collateral damage. If you’re over 50 and on more than three medications, you’re already at risk. Stop blaming the patient. Fix the prescribing culture.

Jay Powers

January 17 2026

My dad had AIN from ibuprofen. He didn’t know he was at risk. We didn’t know. Now he’s on dialysis three times a week. I wish someone had told us earlier. This isn’t just about meds. It’s about listening to your body. If something feels off, don’t ignore it. Don’t wait for a diagnosis. Trust your gut. You know your body better than any algorithm.

Lawrence Jung

January 17 2026

Life is a series of trade-offs. You take a pill to feel better today. Tomorrow, your kidneys pay the price. That’s not a failure of medicine. That’s the cost of modern living. We want instant relief, endless comfort, zero consequences. But biology doesn’t work that way. The body remembers. The kidneys never forget. You can’t outsmart evolution with a prescription.

Sonal Guha

January 11 2026

Stopped omeprazole after my creatinine jumped. Two weeks later, eGFR up 15 points. No biopsy needed. Doctors act like it’s magic when it’s just common sense.