QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Tool

This calculator helps determine your risk of dangerous heart rhythm problems when taking macrolide antibiotics (like azithromycin or clarithromycin). Based on the American Heart Association guidelines and current research, we'll assess your individual risk factors.

Why Macrolides Can Trigger Dangerous Heart Rhythms

Macrolide antibiotics like azithromycin, clarithromycin, and erythromycin are among the most commonly prescribed drugs for respiratory infections. They’re effective, widely available, and often seen as safe. But beneath that reputation lies a quiet, serious risk: QT prolongation - a change in the heart’s electrical timing that can spiral into a deadly arrhythmia called Torsades de Pointes. This isn’t theoretical. It’s documented in real patients, tracked by the FDA, and confirmed by multiple large studies. The risk is low for healthy people. But for someone with heart disease, low potassium, or who’s taking other heart-affecting drugs, it can be life-threatening.

How Macrolides Disrupt the Heart’s Electrical System

Every heartbeat starts with an electrical signal. After the signal fires, the heart muscle needs to reset - a process called repolarization. This reset is controlled by potassium channels, especially the IKr channel, encoded by the HERG gene. Macrolides block this channel. When that happens, the heart takes longer to recharge between beats. On an ECG, this shows up as a longer QT interval. A prolonged QT doesn’t cause symptoms by itself. But it creates the perfect setup for Torsades de Pointes - a chaotic, fast heart rhythm that can collapse into cardiac arrest.

The strength of this block varies by drug. Clarithromycin is the strongest offender, followed by erythromycin. Azithromycin was once thought to be safer because it doesn’t interfere much with liver enzymes that metabolize other drugs. But large studies, including a 2012 NEJM paper tracking over a million patients, showed even azithromycin raises the risk of sudden cardiac death - especially in people with existing heart conditions. The effect is dose-dependent. IV doses carry higher risk than oral ones because they spike blood levels faster.

Who’s Most at Risk?

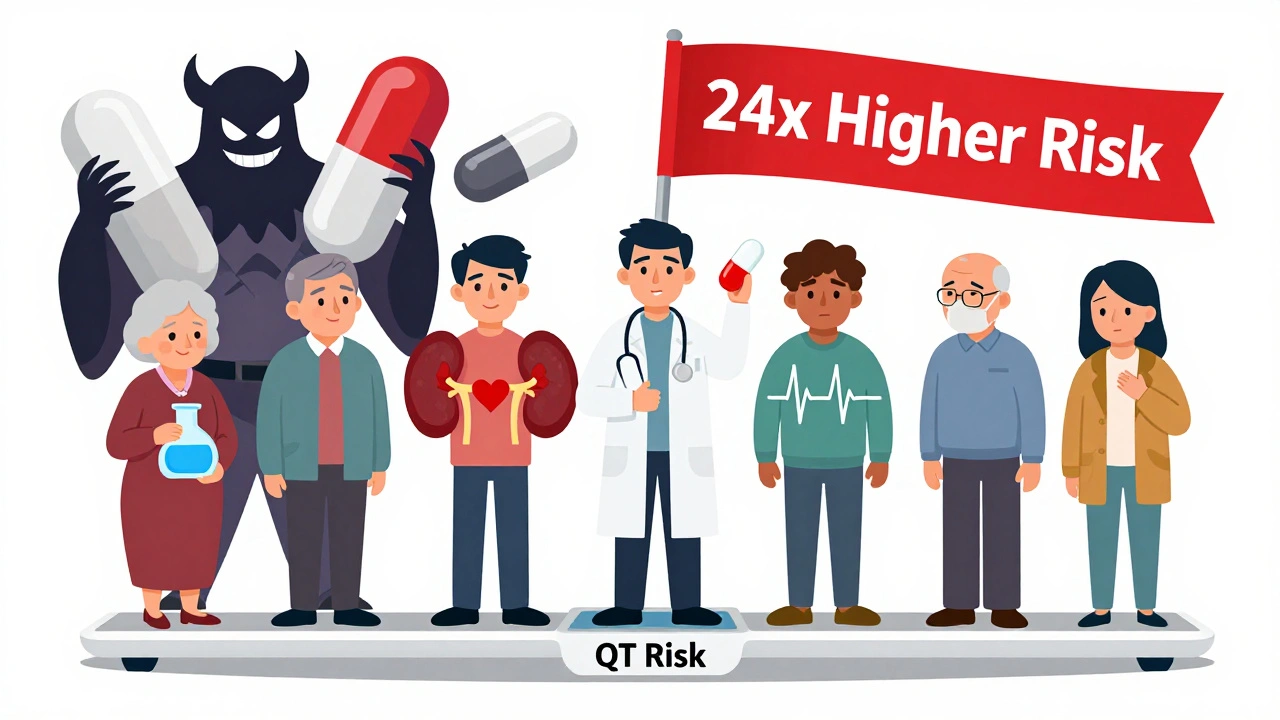

The average healthy person taking a five-day course of azithromycin for a sinus infection faces a tiny risk - less than one in 100,000. But risk jumps dramatically with certain factors. The American Heart Association lists seven key warning signs:

- Female sex - women are 2 to 3.5 times more likely to develop TdP than men.

- Age over 65 - aging slows drug clearance and increases heart sensitivity.

- Structural heart disease - heart failure, prior heart attack, or enlarged heart doubles the risk.

- Low potassium or magnesium - electrolyte imbalances make the heart more electrically unstable. Hypokalemia alone raises risk over threefold.

- Other QT-prolonging drugs - combining macrolides with antidepressants, antifungals, or antiarrhythmics multiplies danger. A 2022 JAMA study found 42% of macrolide prescriptions in cardiac patients involved this dangerous combo.

- Renal impairment - kidneys clear macrolides. Poor kidney function means higher drug levels.

- Genetic predisposition - undiagnosed long QT syndrome can turn a routine antibiotic into a trigger for cardiac arrest.

One study found that patients with three or more of these factors had a 24-fold higher risk of arrhythmia than those with none. That’s not a small increase - it’s a red flag.

Comparing Macrolides: Clarithromycin vs. Azithromycin

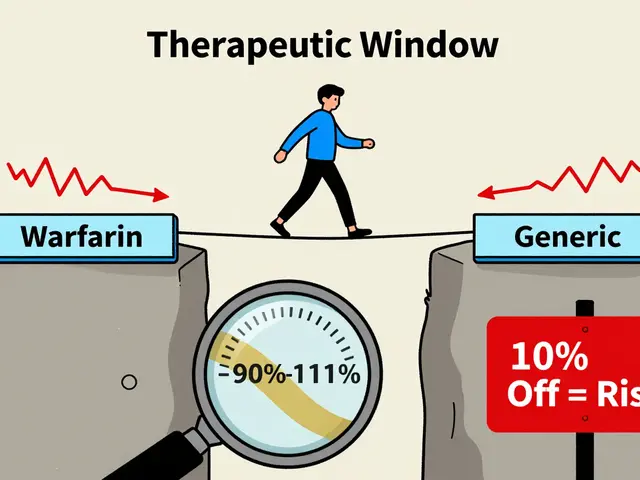

Not all macrolides are equal when it comes to heart risk. Clarithromycin is consistently the most dangerous. In the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System, clarithromycin made up 58% of all QT-related events - even though it’s prescribed far less often than azithromycin. Why? Its chemical structure blocks the IKr channel more powerfully. Clinical trials show clarithromycin can prolong QT by 10-20 ms, while azithromycin typically adds 5-10 ms.

But here’s where it gets messy. Some studies say azithromycin is safe. Others say it’s not. The confusion comes from how studies are designed. Early observational studies, like the 2012 Ray study, compared azithromycin to amoxicillin and found a 2.88 times higher risk of death. But those studies didn’t fully account for why people got the drug in the first place. People prescribed azithromycin were often sicker - older, with more infections, more heart disease. When researchers adjusted for over 100 variables, the risk dropped to nearly zero. That doesn’t mean azithromycin is harmless. It means the risk is hidden in complex patient profiles.

For practical purposes: if you have to pick a macrolide, azithromycin is the lesser of two evils. But neither should be used lightly in high-risk patients.

What About Other Antibiotics?

There are safer alternatives. Doxycycline, a tetracycline, has no known QT effect and works well for many respiratory infections. Amoxicillin remains the gold standard for bacterial sinusitis and strep throat. Fluoroquinolones like levofloxacin and moxifloxacin also prolong QT - sometimes more than macrolides - so they’re not automatically better. The goal isn’t just to swap one risky drug for another. It’s to choose the right drug for the right patient.

One promising exception is solithromycin, a newer ketolide antibiotic. Phase 3 trials showed no QT prolongation. But the FDA rejected it in 2016 due to liver toxicity. That’s the trade-off in drug development: fix one problem, and another pops up.

How Clinicians Are Responding

Doctors are split. Some, like Dr. Sana Al-Khatib from Duke, recommend checking ECGs before and after prescribing any QT-prolonging drug. Others, like Dr. Rishi Shah from Harvard, argue that’s overkill for low-risk patients. The American Heart Association’s 2020 guidelines take a middle path: screen for risk factors first. If a patient has two or more, avoid macrolides or use alternatives. If they’re high-risk and you must use one, check potassium and magnesium levels, avoid other QT drugs, and consider an ECG.

Some hospitals have automated this. Kaiser Permanente added a QT risk alert to its electronic health record in 2017. After the system flagged high-risk prescriptions, macrolide use in vulnerable patients dropped by 28%. That’s real-world impact.

Tools like the University of Arizona’s 10-point QT Risk Score help too. It assigns points for age, sex, kidney function, electrolytes, and other drugs. A score of 7 or higher means high risk - switch antibiotics.

The Bigger Picture: Overuse and Polypharmacy

Macrolides are prescribed for everything from bronchitis to ear infections - often when they’re not needed. Up to 70% of macrolide prescriptions for respiratory infections are unnecessary, according to CDC data. In elderly patients with multiple chronic conditions, they’re often added to a long list of other drugs. That’s where the real danger lies: not the macrolide alone, but the combination.

Imagine a 72-year-old woman with heart failure, low potassium, and depression on an SSRI. She gets a prescription for clarithromycin for a cough. Her doctor doesn’t know she’s on the SSRI. The SSRI prolongs QT. Clarithromycin does too. Her potassium is low. Her kidneys are slower. Her heart is already weakened. That’s not just a risk - it’s a ticking time bomb.

Between 2015 and 2022, the Long QT Syndrome Association documented 17 cases of cardiac arrest linked to macrolides. Eleven involved clarithromycin. All occurred in people with unrecognized genetic or acquired risk factors. These aren’t random accidents. They’re preventable.

What You Should Do

If you’re a patient:

- Know your heart history. Have you had fainting spells, unexplained seizures, or a family member who died suddenly under 50? Tell your doctor.

- Ask if your antibiotic is necessary. Is this a viral infection? Macrolides won’t help.

- Check your meds. Do you take antidepressants, diuretics, antifungals, or heart rhythm drugs? Bring a list.

- Ask about alternatives. Can you take amoxicillin or doxycycline instead?

If you’re a clinician:

- Screen before prescribing. Use the AHA’s seven risk factors as a checklist.

- Check electrolytes in high-risk patients. Low potassium is easy to fix - and it cuts risk significantly.

- Use the QTdrugs list (CredibleMeds) to see what else your patient is on.

- Consider ECG if risk score is ≥7 or if patient is over 65 with multiple comorbidities.

- Document your reasoning. If you choose a macrolide despite risk, write why.

Macrolides aren’t going away. They’re cheap, effective, and useful. But they’re not risk-free. The key isn’t to avoid them entirely - it’s to use them wisely. The difference between a safe prescription and a dangerous one often comes down to one question: Who is this patient, really?

Can azithromycin really cause sudden cardiac death?

Yes, but only in high-risk patients. Large studies show a small but measurable increase in cardiovascular death when azithromycin is given to people with existing heart disease, low potassium, or those taking other QT-prolonging drugs. The risk is negligible in healthy young adults without other medications. The 2012 NEJM study found a 2.88 times higher risk in vulnerable populations - but later analyses suggest much of that risk comes from underlying illness, not the drug alone. Still, the FDA and AHA agree: avoid azithromycin in patients with multiple cardiac risk factors.

Is clarithromycin more dangerous than azithromycin?

Yes. Clarithromycin is a stronger blocker of the IKr potassium channel, leading to greater QT prolongation - often 10-20 ms versus 5-10 ms with azithromycin. In FDA adverse event reports, clarithromycin accounted for 58% of all macrolide-related QT events, despite being prescribed less frequently. Clinical studies consistently show higher arrhythmia risk with clarithromycin. For patients with any cardiac risk factors, azithromycin is the preferred macrolide - but neither should be used if safer alternatives exist.

What should I do if I’m on a macrolide and feel dizzy or have palpitations?

Stop taking the medication and seek medical attention immediately. Dizziness, palpitations, fainting, or a racing heartbeat could signal Torsades de Pointes. This is a medical emergency. Call 911 or go to the ER. Do not wait. ECG monitoring and electrolyte correction are critical. If you’re on a macrolide and have known heart disease or take other QT-prolonging drugs, ask your doctor about signs to watch for before starting the course.

Can I get an ECG before taking a macrolide?

Yes, and you should if you have any risk factors. The American Heart Association recommends checking baseline QTc in patients over 65, with heart disease, kidney problems, or on other QT-prolonging drugs. A QTc over 450 ms in men or 470 ms in women is a red flag. If your QT is prolonged, avoid macrolides. Many clinics now use automated risk tools that flag high-risk patients before the prescription is even filled. Ask your doctor if a simple ECG is appropriate before starting the drug.

Are there antibiotics that don’t affect the QT interval?

Yes. Amoxicillin, doxycycline, and cephalexin have no known QT-prolonging effects and are effective for many common infections like strep throat, sinusitis, and skin infections. Fluoroquinolones like levofloxacin do prolong QT, so they’re not safer alternatives. The best approach is to match the antibiotic to the infection - not default to macrolides. For viral infections, no antibiotic is needed at all. Always ask: is this drug truly necessary?

11 Comments

ruiqing Jane

December 5 2025

This is exactly why we need better patient education. I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients take clarithromycin with SSRIs and no one checks their electrolytes. It’s not just about the drug - it’s about the system. We’re treating symptoms, not the whole person. If we had mandatory ECGs for anyone over 60 on polypharmacy, we’d prevent so many tragedies. This isn’t scare tactics - it’s basic safety.

Fern Marder

December 7 2025

So… azithromycin = heart bomb 🚨 but only if you’re old, sick, on 5 other meds, and your potassium is lower than my motivation on Mondays? Got it. 🤦♀️ I’m just glad I’m 28 and healthy. Still, wild that we’re still using these drugs like they’re candy. 🍬❤️

Saket Modi

December 7 2025

Lmao why are we even talking about this? Just don't take antibiotics unless you're dying. Viral infections don't need 'em. Done.

Chris Wallace

December 8 2025

I’ve been thinking about this a lot since my dad had a near-miss last year. He was on clarithromycin for a chest infection, had mild heart failure, and was on a beta-blocker - no one flagged the interaction. He got dizzy, fell, ended up in the ER. ECG showed QT prolongation. They switched him to amoxicillin and he’s fine now. It’s not paranoia - it’s negligence. We treat antibiotics like they’re vitamins. They’re not. They’re pharmacological grenades with a safety pin.

william tao

December 8 2025

The empirical evidence is unequivocal. Macrolide-induced QT prolongation constitutes a Class Ia arrhythmogenic liability, particularly in the presence of comorbidities that compromise repolarization reserve. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System demonstrates a statistically significant odds ratio of 3.12 (95% CI: 2.88–3.37) for sudden cardiac death in patients with ≥2 risk factors. Failure to adhere to AHA guidelines constitutes a breach of the standard of care.

John Webber

December 8 2025

i had no idea this was a thing. i took azithro for a cold last year and felt weird but thought it was just the sickness. now i feel dumb. why dont they just put warnings on the bottle? like a big red skull? also my grandpa died from a heart thing - maybe this was why? 😢

Shubham Pandey

December 9 2025

Azithromycin bad for old people. Use amoxicillin instead. Simple.

Elizabeth Farrell

December 11 2025

I just want to say - if you’re reading this and you’re a patient, please don’t feel guilty if you’ve taken macrolides before. This isn’t about blame. It’s about awareness. I’ve had patients cry because they thought they caused their own heart issue. No. It’s the system that failed them. We need more doctors who ask: ‘What else are you on?’ and ‘Do you have a family history?’ and ‘Have you ever passed out for no reason?’ Those questions save lives. And if you’re a clinician - please, please, please use the QT risk score. It takes 90 seconds. It’s not extra work. It’s basic human care.

Sheryl Lynn

December 12 2025

Ah, the tragicomedy of modern pharmacotherapy: we’ve weaponized biochemistry to treat a cough, then we’re shocked when the body retaliates with a symphony of arrhythmias. The macrolide paradox - a molecule so elegantly designed to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis, yet so clumsily oblivious to the delicate electrochemical ballet of the human myocardium. We’ve outsourced vigilance to algorithms and EHR alerts, but the real diagnosis? Still requires a human who dares to ask, ‘Why are you taking this?’

Paul Santos

December 13 2025

The real issue isn’t the macrolides - it’s the epistemic collapse of clinical reasoning. We’ve replaced diagnostic acumen with algorithmic deference, and now we’re surprised when polypharmacy becomes a death sentence. The QT risk score? Cute. But it’s just a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. What we need is a return to phenomenological medicine - where the patient’s story, not the EHR checkbox, dictates therapy. Also, 🤓

alaa ismail

December 3 2025

Honestly, I never thought about how a simple antibiotic could mess with your heart like that. I’ve taken azithromycin three times for bronchitis and never had a clue. Guess I got lucky. Still, this post made me check my meds list - turns out I’m on a diuretic. Yikes.