Dipyridamole vs Alternatives: Medication Selector

Use this tool to compare dipyridamole with its alternatives based on clinical use cases, side effects, and drug interactions.

Recommended Antiplatelet Therapy

Dipyridamole

This combination is recommended based on your profile.

Alternative Options

Clopidogrel

P2Y12 receptor blocker, ideal post-stent or for GI sensitivity.

Ticagrelor

Reversible P2Y12 blocker with fast onset for acute events.

About Dipyridamole

Dipyridamole is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that increases cAMP in platelets and boosts adenosine levels. It's often combined with aspirin for stroke prevention and used in cardiac stress tests.

When your doctor talks about “antiplatelet therapy,” you might hear a name you’ve never seen before - dipyridamole. It’s a classic drug, but it’s not the only option. Below we break down how dipyridamole works, what it’s used for, and how it stacks up against the most common alternatives like clopidogrel, aspirin, and ticagrelor. By the end you’ll know which medication fits your health situation best.

What is Dipyridamole?

Dipyridamole is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that prevents platelets from clumping together. First approved in the 1960s, it’s most often combined with aspirin for stroke prevention, and it’s also used during cardiac stress testing to improve blood flow.

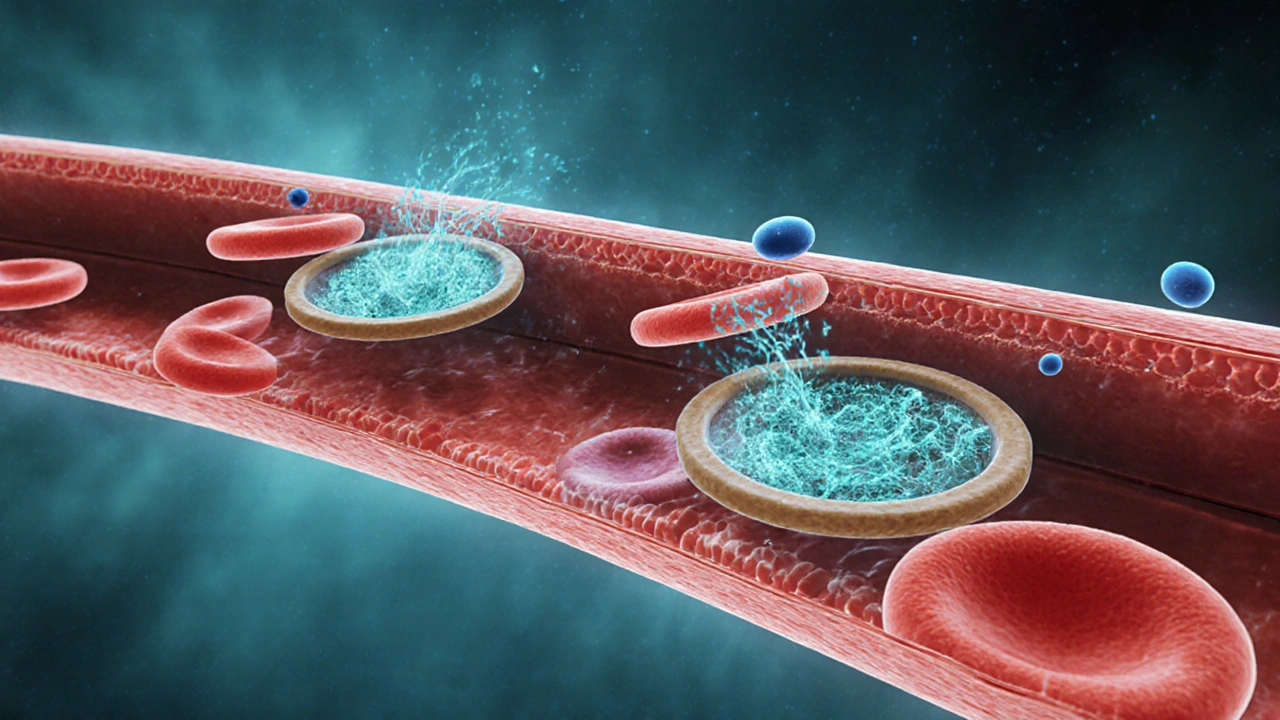

How Dipyridamole Works

- Increases cAMP: By blocking the breakdown of cyclic AMP inside platelets, dipyridamole keeps them in a relaxed state.

- Boosts adenosine: It inhibits the uptake of adenosine, a natural vasodilator, which widens blood vessels and improves oxygen delivery.

- Synergy with aspirin: When paired with aspirin, the two drugs cover different pathways in platelet activation, providing stronger protection against clots.

Key Clinical Uses

- Secondary prevention of ischemic stroke (often as dipyridamole‑aspirin combo).

- Pharmacologic stress testing for myocardial perfusion imaging.

- Off‑label use in some patients with peripheral arterial disease.

Common Alternatives at a Glance

Below are the main drugs doctors consider when they need an antiplatelet effect.

- Clopidogrel - a P2Y12‑receptor blocker often used after stent placement.

- Aspirin - the oldest antiplatelet, works by irreversibly inhibiting COX‑1.

- Ticagrelor - a reversible P2Y12 inhibitor with a faster onset than clopidogrel.

- Cilostazol - a phosphodiesterase‑3 inhibitor used mainly for intermittent claudication.

- Warfarin - a vitamin‑K antagonist, technically an anticoagulant rather than an antiplatelet.

- Heparin - a parenteral anticoagulant used in acute settings.

Side‑Effect Profiles Compared

| Drug | Main Mechanism | Common Side Effects | Major Drug Interactions | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dipyridamole | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor, boosts adenosine | Headache, dizziness, gastrointestinal upset | Increases bleeding risk with warfarin; can raise aspirin‑related GI irritation | Stroke secondary prevention (with aspirin), cardiac stress testing |

| Clopidogrel | P2Y12‑receptor blocker | Bleeding, rash, rare thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | Reduced effect with CYP2C19 inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole) | Post‑PCI, acute coronary syndrome, peripheral artery disease |

| Aspirin | Irreversible COX‑1 inhibitor | GI bleeding, ulceration, tinnitus at high doses | Enhanced bleeding with anticoagulants, NSAIDs | Primary/secondary prevention of MI, stroke, PCI prophylaxis |

| Ticagrelor | Reversible P2Y12 blocker | Dyspnea, bleeding, bradyarrhythmias | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors raise levels; avoid with severe asthma | ACS, post‑stent therapy when rapid platelet inhibition needed |

| Cilostazol | Phosphodiesterase‑3 inhibitor | Headache, palpitations, diarrhea | Contraindicated with severe heart failure | Intermittent claudication, secondary stroke prevention (Europe) |

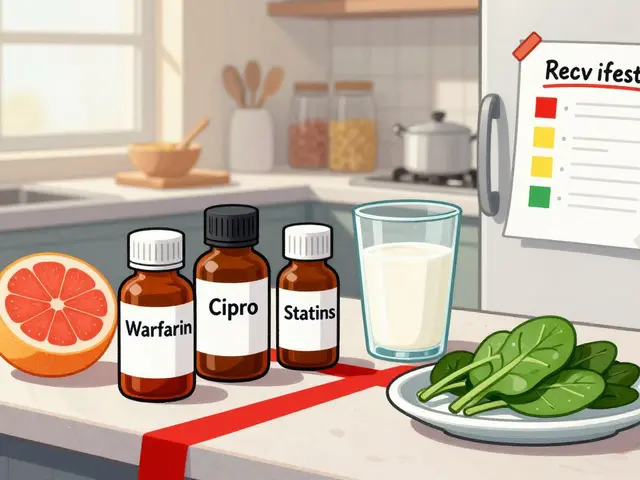

| Warfarin | Vitamin‑K antagonist | Bleeding, skin necrosis, teratogenicity | Numerous food and drug interactions (e.g., leafy greens, antibiotics) | Mechanical heart valves, atrial fibrillation, VTE |

| Heparin | Activates antithrombin III | Bleeding, heparin‑induced thrombocytopenia | Concurrent use with other anticoagulants amplifies bleeding | Hospital‑based anticoagulation, peri‑procedural bridging |

Choosing the Right Agent: Decision Criteria

Here’s a quick cheat‑sheet to help you (or your clinician) decide when dipyridamole makes sense versus when an alternative is smarter.

- Stroke prevention with aspirin already on board? Adding dipyridamole boosts protection without needing a brand‑new drug class.

- History of gastrointestinal bleeding? Aspirin‑dipyridamole may worsen irritation; clopidogrel or ticagrelor can be gentler on the stomach.

- Need rapid platelet inhibition (e.g., after a heart attack)? Ticagrelor achieves effect in <30minutes, while dipyridamole takes days to reach steady state.

- Concern about drug interactions? Dipyridamole’s main issue is synergy with other antithrombotics; clopidogrel is affected by CYP2C19 genetics.

- Cost sensitivity? Generic dipyridamole‑aspirin combos are usually cheaper than ticagrelor or branded clopidogrel.

Practical Tips & Pitfalls

Even the best drug can cause trouble if not used correctly. Keep these pointers in mind:

- Adherence matters. Dipyridamole is taken twice daily. Missed doses can spike platelet activity.

- Watch for headaches. They’re the most common complaint; a slow titration or adding a mild analgesic often helps.

- Avoid abrupt discontinuation before surgery. Like other antiplatelets, stop dipyridamole 5‑7 days prior to major procedures to reduce bleeding risk.

- Check kidney function. The drug is partially excreted renally; dose adjustment may be needed in severe impairment.

- Genetic testing isn’t needed. Unlike clopidogrel, dipyridamole’s effect isn’t influenced by CYP polymorphisms.

Summary of When Dipyridamole Shines

- Patients already on aspirin for stroke prevention who can tolerate extra dosing.

- Those who need a non‑P2Y12 antiplatelet (e.g., after aspirin intolerance).

- Individuals looking for a low‑cost, well‑studied option with a solid safety record.

When to Prefer an Alternative

- Acute coronary syndrome where fast, potent inhibition is vital - ticagrelor or clopidogrel.

- History of severe bleeding or peptic ulcer disease - consider single‑agent clopidogrel or a reduced‑dose aspirin regimen.

- Patients with severe heart failure - avoid cilostazol and choose a P2Y12 blocker.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take dipyridamole without aspirin?

Yes, dipyridamole can be prescribed alone, but its strongest evidence comes from the dipyridamole‑aspirin combo for secondary stroke prevention. If you can’t tolerate aspirin, your doctor may choose another antiplatelet instead.

How quickly does dipyridamole start working?

It reaches therapeutic levels after about 2‑3 days of twice‑daily dosing, and steady‑state platelet inhibition is typically seen after a week.

Is dipyridamole safe during pregnancy?

It’s classified as pregnancy‑category B in the UK, meaning animal studies showed no risk but human data are limited. Most clinicians avoid it unless the benefit clearly outweighs potential risks.

What should I do if I get a severe headache on dipyridamole?

Report it to your doctor right away. Often a dose reduction, slower titration, or adding a simple analgesic like acetaminophen can control the headache without stopping the drug.

How does dipyridamole differ from cilostazol?

Both raise cAMP, but dipyridamole works mainly by blocking adenosine reuptake, while cilostazol directly inhibits phosphodiesterase‑3. Cilostazol is approved for intermittent claudication, not stroke prevention, and it’s contraindicated in severe heart failure.

10 Comments

Darin Borisov

October 13 2025

The pharmacodynamic profile of dipyridamole, as delineated in contemporary hemostatic literature, epitomizes a quintessential archetype of phosphodiesterase inhibition that concomitantly augments endogenous adenosine bioavailability. Such mechanistic duality potentiates vasodilatory cascades whilst attenuating platelet aggregatory pathways, thereby engendering a synergistic paradigm when co-administered with cyclooxygenase-1 blockade. Nevertheless, the therapeutic window is circumscribed by a constellation of adverse phenotypes, most notably cephalgia, vestibular disturbances, and gastrointestinal dyspepsia, which collectively attenuate patient adherence. From a guideline-concordant perspective, the American Heart Association’s 2022 consensus relegates dipyridamole to a subordinate tier in secondary stroke prophylaxis, reserving its utilization for patients with contraindications to the more robust P2Y12 inhibitors. Clopidogrel, by virtue of its irreversible P2Y12 antagonism, confers a more predictable antithrombotic efficacy and a comparatively benign gastroenterological profile, rendering it the de facto first-line agent in myriad clinical vignettes. Conversely, ticagrelor’s reversible binding kinetics and accelerated onset of action furnish a strategic advantage in acute coronary syndromes, albeit at the expense of dyspneic sequelae attributable to adenosine reuptake inhibition. Pharmacogenomic considerations further complicate the therapeutic calculus, with CYP2C19 polymorphisms attenuating clopidogrel activation and thereby mandating alternative regimens in carriers of loss-of-function alleles. In juxtaposition, dipyridamole’s metabolism is relatively insulated from cytochrome P450 variability, which may be an asset in pharmacoresistant cohorts. However, the drug’s propensity to potentiate the antiplatelet effect of concomitant aspirin escalates hemorrhagic risk, a factor that merits meticulous risk-benefit stratification. Economic analyses reveal that while dipyridamole is generically inexpensive, the ancillary costs associated with monitoring and management of its side-effect spectrum may erode its fiscal advantage. From a patient-centric standpoint, the tolerability profile is paramount; the prevalence of bothersome headache in upwards of twenty percent of recipients often precipitates premature discontinuation. Clinical trials, such as the European Stroke Prevention Study, have illuminated marginal incremental reductions in recurrent ischemic events when dipyridamole is appended to aspirin, yet these gains are frequently offset by adverse event burden. Moreover, the regulatory landscape sanctions dipyridamole primarily for stroke secondary prevention and pharmacologic stress testing, limiting its applicability across broader thromboembolic pathologies. In practice, clinicians frequently resort to a heuristic whereby dipyridamole is selected for patients with a low bleeding risk profile and a predilection for oral therapy over injectable agents. Ultimately, the decision matrix necessitates an integrative appraisal of pharmacological efficacy, safety tolerability, patient comorbidities, and socioeconomic considerations.

Sean Kemmis

October 19 2025

Dipyridamole is overrated.

Nathan Squire

October 25 2025

Ah, the ever‑ever‑glorious dipyridamole-nothing says “cutting‑edge medicine” quite like a drug that was discovered before most of us were born. It does its job in the right niche, namely when you need a modest boost to aspirin’s antiplatelet effect without venturing into the territory of expensive new agents. However, if you’re already juggling a bleeding risk, adding another platelet inhibitor is akin to sprinkling salt on an already burnt steak. In short, stick with it only when the specific clinical criteria line up, otherwise consider the newer P2Y12 inhibitors.

Ted Whiteman

October 30 2025

Honestly, the hype around dipyridamole feels like a misguided nostalgia trip; who needs a drug that makes you dizzy just to prevent a stroke? I’d rather trust the newer agents that actually move the needle without the headache.

Dustin Richards

November 5 2025

Hey folks, I get why you’re confused-these meds have a lot of overlap. If you’re prone to stomach issues, dipyridamole plus aspirin can be rough, so a drug like clopidogrel might be kinder on your gut. On the other hand, if you need fast action after a heart attack, ticagrelor’s quick kick could be what you want. Talk with your doctor about your personal risks and preferences.

Vivian Yeong

November 11 2025

The article glosses over the real downside: dipyridamole’s side‑effect burden often outweighs its modest benefit. For most patients, a newer P2Y12 inhibitor is a smarter choice.

suresh mishra

November 17 2025

Dipyridamole works best when combined with aspirin for secondary stroke prevention; otherwise, clopidogrel is generally preferred due to fewer GI complaints.

Vinay Keragodi

November 22 2025

Just a heads‑up, if you’ve got asthma, ticagrelor can make breathing a bit tricky, so dipyridamole might actually be the safer bet. Also, keep an eye on any headache-sometimes it’s just the med kicking in, not something serious. Bottom line: match the drug to your own health story, not just the textbook.

Cassidy Strong

November 28 2025

While dipyridamole, indeed, offers a historically validated mechanism of action, it, however, is frequently accompanied by a cascade of adverse events-headaches, dizziness, and gastrointestinal discomfort-that, in many cases, compel patients to discontinue therapy; consequently, clinicians must weigh these factors meticulously, especially when alternative agents, such as clopidogrel or ticagrelor, present comparable efficacy with a more favorable side‑effect profile.

John Blas

October 7 2025

Wow, the whole dipyridamole thing feels like a relic from the stone age, yet they keep pushing it like it’s the holy grail of stroke prevention.